Identifying shunt failure mechanisms in neurological disease treatments

Hydrocephalus is a condition in which an accumulation of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) on the brain causes increased pressure in the skull. It affects approximately one million people in the U.S., including one out of every 1,000 newborns.

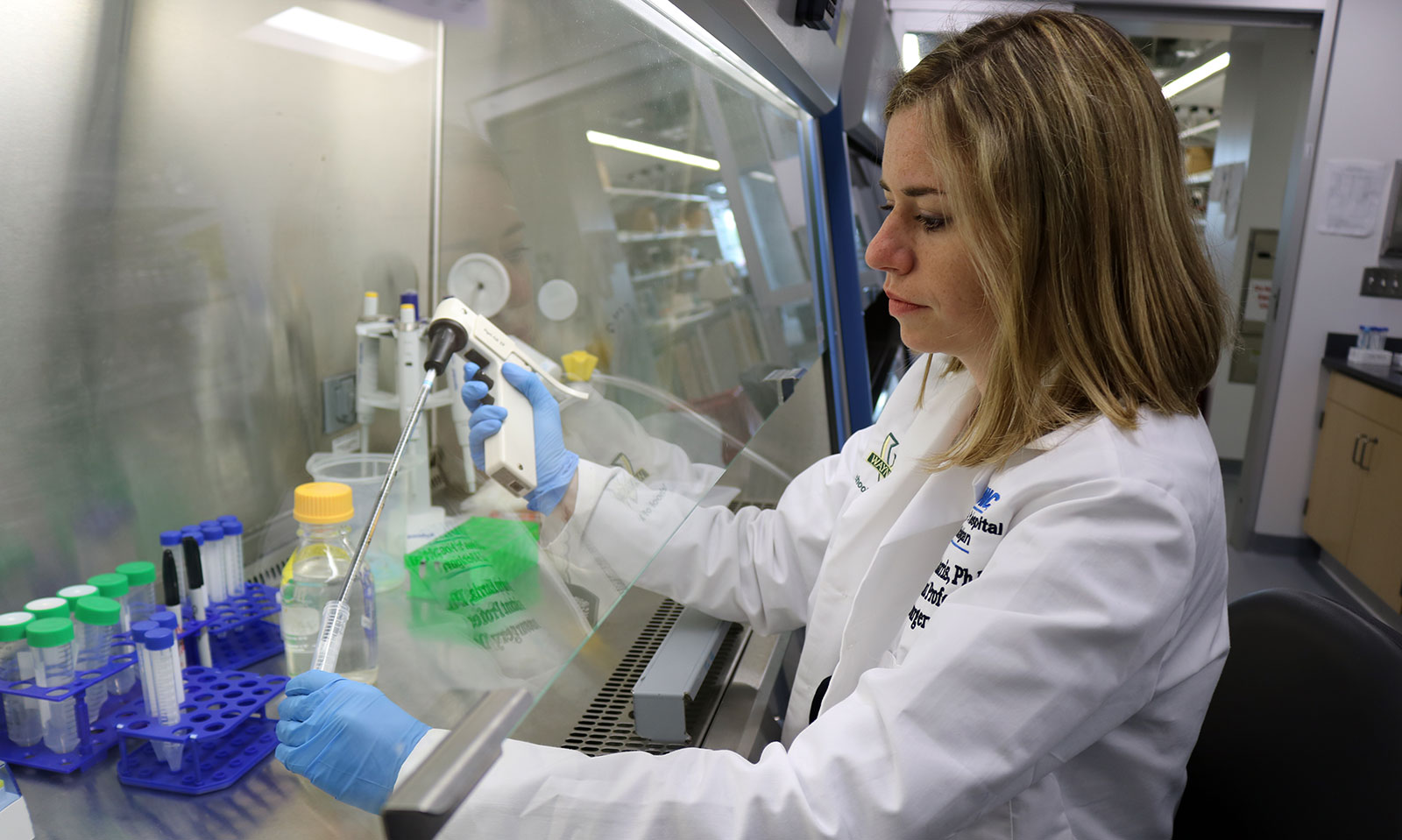

The only effective treatment of hydrocephalus is surgery and usually involves placement of a shunt system. Carolyn Harris, professor of chemical engineering and materials science at Wayne State, is a renowned expert on neurological disorders such as hydrocephalus, and has sought to evaluate and improve shunt designs.

Shunts reduce intracranial pressure by generating a pathway to drain excess CSF from the brain, but complications often occur-an estimated 50 percent of shunts in pediatric patients fail within two years. Harris notes that shunts can disconnect, become infected, develop blockages due to infiltrating cells or tissues, or create other reactions due to it being a foreign body with no physiological properties.

"How these responses occur and what we can do to reduce the incidence of shunt blockage are keys to improving patient care," said Harris.

These phenomena are not well understood because of variances in cell type and activity across patient subpopulations. Astrocytes and microglia are predominant in response to shunt systems because they bind directly to the catheter and create an environment for other cells to adhere. Harris's lab fabricated 3-D hydrogel scaffolds to model shunt failure due to cell and tissue obstruction, with the data indicating that cell migration may begin around the shunt inlet holes.

"When we know the mechanisms that drive cell attachment and activity on the shunt, we will be able to define strategies for biology-driven engineering improvements," said Harris, who noted that in more than 60 years since the inception of the shunt, fewer than 40 substantial modifications have been implemented to inhibit blockage, and none have produced significant improvements in treatment.